John Eliot: Father of “Praying Villages”

With the exception of the Vikings, the primary European Colonizers to the Americas brought with them priests and other religious acolytes for the purpose of converting the native people to the Christian religion. The Spanish came with soldiers and priests to conquer and convert. The French came with trappers and priests to trade and convert. The English came with settlers, followed by missionaries. One of the most well-known missionaries in New England was John Eliot. Eliot was born in Widford, Hertfordshire in 1604; the year after the death of Elizabeth I and beginning of the reign of James I (James VI of Scotland).

While Elizabeth followed the Church of England and was considered a tolerant and worldly leader, James was brought up by John Knox, a radical Puritan (referring to those who wished to purify the Church of England of all things Catholic). James would become known as the patron who supported the publication of the Bible, known as the King James Bible. James would change the tone of the monarchy and the first English colonization to North America would take place under his reign.

John Eliot was 27 when he left England and came to Boston, which was founded just the year before. By 1632, Eliot would move to the new town of Roxbury and found a church (First Church) there as well as a school (the Roxbury Latin School). Although Eliot would preach in his Roxbury church until his death in 1690, he believed his true calling was to convert the local indigenous people to Christianity.

Once Eliot decided to convert the local indigenous people, he had to overcome the language barrier. In a letter dated February 12,1649, Eliot wrote ‘There is an Indian living with Mr. Richard Calicott of Dorchester who was taken in the Pequott warres, though belonging to Long Island.. This Indian is ingenious, can read, and I taught him to write, which he quickly learnt, though I know not what use he maketh of it. He was the first I made use of to teach me words and to be my interpreter. Eliot also found another young native man, whom he described as “a pregnant witted young man, who had been a servant in an English house, who pretty well understood our Language, better than he could speak it, and well understood his own language: and hath a clear pronunciation”

Crediting God and divine intervention, Eliot and his interpreter would slowly “translate” the Bible into Algonquin, which is the major language group of the indigenous people of the New England coastal areas. As the tribes had no written language, the books were written phonetically, designed for missionaries to read allowed to the tribes along with native interpreters to assist in the conversion of tribal members to Christianity.

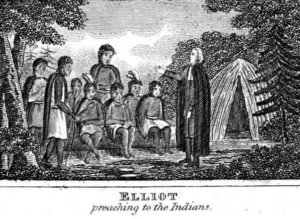

Using the “translated” Bible, other religious texts and native interpreters, John Eliot began to convert local tribal members to Christianity. Eliot was very much a product of his time in that he equated ‘being a good Christian” with “being a good Englishman”. Mirroring the later (19th/20th Century) “Indian Schools”, Eliot isolated the converted from their homes, family and culture. They were forced to cut their hair and wear English clothing and were isolated in villages, patterned after English towns, which were known as “Praying Towns.” The inhabitants, known as “praying Indians”, were sequestered in 14 different towns with, in 1674, a total of 1100 inhabitants.

Although the “Praying Villages” were allied with the English, when King Phillips War (aka Metacomet’s War, as the name “Phillip” was an English name given to Metacomet, a Wampanoag) broke out in 1675, it mattered not that these villages were allies. Metacomet and his warriors, starting in the Plymouth colony and ranging north and west ravaged the country, destroying whole towns and settlements and killing the inhabitants. When the people of Boston, looked at the “praying villages” they did not see allies, but potential converts for Metacomet. In order to prevent them joining Metacomet – although there was no evidence that they would do so – native inhabitants all over Massachusetts, including the “praying towns” were rounded up and placed in so called concentration camps. The people of the “praying village” of Natick were rounded up, put on boats and taken out to Deer Island, where the currents were too strong for even the most able swimmer to make it back to the mainland.. Just to make sure no one escaped, many of the younger, stronger men were captured and sold into slavery in the Caribbean. Those two hundred or so women, children and old men were left on the island with only what they could carry. Most of them, who were members of the Nipmuck tribe, perished when they were finally allowed off the island several months later.

Eliot attempted to intervene and save his “praying Indians” but the fear was too great from the colonists. Ten of the 14 “praying villages were totally destroyed. Native participants were sold into slavery and women and children were “indentured” to English homes as servants. In Rhode Island, the Narragansetts who did not join with Metacomet were nonetheless ambushed in the Great Swamp in Southern RI, killing hundreds of old men, women and children.

Although some remnants of the “praying villages” would survive into the 18th Century, Eliot’s attempts to Christianize (and make more English) the native people, would fade. But the concept of conversation of indigenous people to western culture by destroying their native culture would return in the 19th and 20th centuries with the “Indian Schools”. In these “schools”, native children from all over the United States were sent to “Kill the Indian. Save the man”. Large numbers of native children from Massachusetts and surrounding areas were sent to the Carlisle School in Pennsylvania. Similar “schools” operated in Canada and Australia.

To learn more about the “Indian Schools”, watch Dawnland: https://dawnland.org

References:

The Life of John Eliot: with an account of the early missionary efforts among the Indians of New England. Nehemiah Adams. Boston. 1870

John Eliot’s First Indian Interpreter, Cockenoe-de-Long Island and the Story of his Career from the Early Records. William Wallace Tooker: London. Henry Stevens’ Son and Stiles. 1896