Rainsford Island and the Bell Post G.A.R.

Black Heritage and Boston Harbor: Part 2

Rainsford Island and the Bell Post G.A.R.

“Honor to the soldier and sailor everywhere, who bravely bears his country’s cause. Honor, also, to the citizen who cares for his brother in the field and serves, as he best can, the same cause.”

― Abraham Lincoln

In the decades spanning 1850-1870, the population of the City of Boston skyrocketed like never before. During this time, the city itself physically expanded as it incorporated surrounding towns and filled in shallow water areas, creating more land. It also saw one of the first surges of immigration of America’s Industrial Era, with a significant influx of Irish immigrants. In the latter years of this period, countless soldiers returned from the Civil War—many of whom sustained life-changing injuries and traumas during their service. Many people—veterans, immigrants, and civilians alike—were unable to find or maintain employment to support themselves and their families. As such, Boston’s unhoused population also grew.

An 1852 Act sought to mitigate these concerns by establishing a hospital and almshouse on Rainsford Island in Boston Harbor. Rainsford had previously been used as a smallpox quarantine hospital, and already had buildings that could support a new public health program. Unfortunately, the new facilities suffered from insufficient funding and oversight, and they quickly fell into a state of neglect. By 1864 when Civil War veterans began arriving on the island, Rainsford was already a site of rampant infectious disease, medical malpractice, and severe overcrowding . Despite several laws in place to support and care for veteran’s at the time, the people sent to Rainsford Island were treated just as appallingly as the other patients, with very little documentation of individuals’ arrivals, treatments, discharges, or deaths. People who arrived at Rainsford simply as military veterans seeking medical support, were, “left to become legally paupers.” The inhumane conditions, combined with an overall financial deficit for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts led to the temporary closure of Rainsford Island facilities on December 31, 1866.

“Rainsford’s Island, Boston Harbor” Robert Salmon, ca.1840

Image courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Depiction of Rainsford Island prior to its use as an almshouse and veterans home. At the time of the painting, the building was a smallpox hospital.

In 1872, the City of Boston purchased Rainsford Island and its facilities, assuming ownership from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The almshouse and hospital doors were once again opened to Boston’s male ‘paupers.’ The facilities primarily housed Black veterans and Irish immigrants, and were inadequate, outdated, and severely overcrowded. In addition, those living on the island who were healthy enough were required to “provide labor,” primarily by breaking rocks and other stone-cutting tasks, which ultimately served as a source of financial profit for the City of Boston.

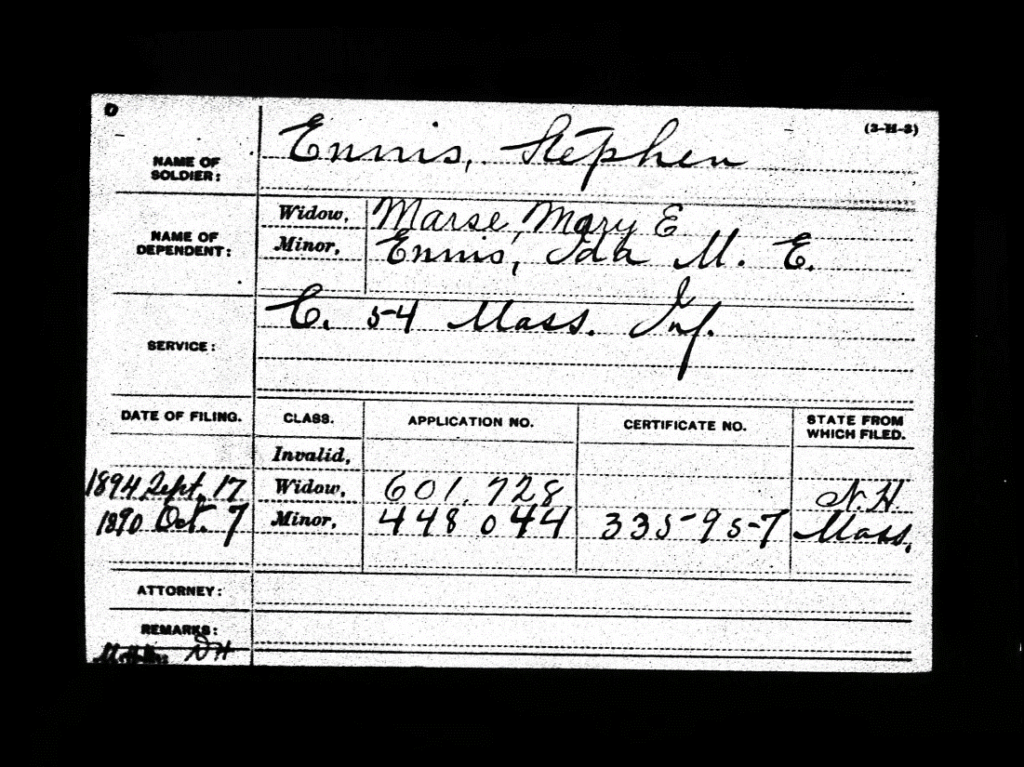

In 1882, surviving veterans on Rainsford were transferred to a veteran’s home in Chelsea, Massachusetts; however, many had died and were buried on the island over the course of the previous decade. Exact numbers are not known, but it is believed that approximately 100-120 Civil War veterans were buried on Rainsford Island. One of these veterans was Stephen Ennis, a musician in the Massachusetts 54th Volunteer Infantry. Records show that Ennis discharged from the military upon the expiration of his term in 1865. He died of phthisis (tuberculosis) on Rainsford Island on August 12, 1882. Ennis was survived by his wife, Mary E. Marse, and his daughter, Ida M. E. Ennis.

Military Dependent Card listing Stephen Ennis of the 54 Mass Infantry, his widow, and minor.

Image courtesy of Bill McEvoy

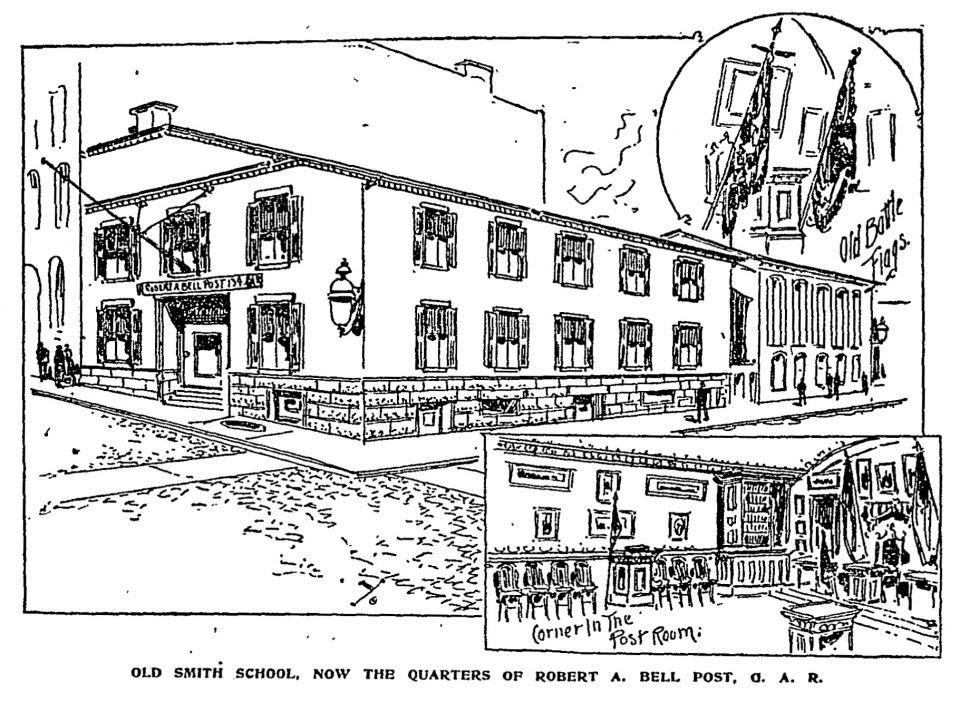

Meanwhile, on the mainland, the Smith School on Beacon Hill was leased to the Robert A. Bell Post, 134, of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.)–an organization which fostered community among veterans. The members of this specific G.A.R. post were primarily Black veterans, including those of the Massachusetts 54th and 55th Volunteer Infantry regiments. Members of the Bell Post G.A.R. organized events and gatherings to support the local Black community, to recognize the importance of Black veterans and their families to the Union Army, and to continue the fight against racial injustice.

Between 1882 and 1933, the Bell Post G.A.R. participated in a Memorial Day commemoration event, in which members traveled out to Rainsford Island to lay flowers on the graves of their comrades. Members of the Women’s Relief Corps—a division of the G.A.R.—also attended the ceremony, tossing flowers into the harbor to honor unknown soldiers. In some years, other veterans groups and organizations like the Shaw Guards and the William H. Carney Camp, 82, Sons of Veterans joined the Bell Post G.A.R. in their Memorial Day ceremonies. The commemorations held by Black veterans emphasized their camaraderie and community, and challenged ongoing racist ideologies in the United States. They also served as a form of protest and activism by refusing to allow those who were mistreated and died at Rainsford Island to be forgotten.

Print of the “Old Smith School, Now the Quarters of the Robert A. Bell Post, G.A.R..”

Image courtesy of Daily Boston Globe, October 9, 1900.

In 1948, the City of Boston unveiled a plaque in memory of 79 Civil War veterans at Long Island Cemetery, following discussions of reinterring burials from Rainsford Island to this site. However, there are inconsistencies between the names on the plaque and names of soldiers known to have been buried on Rainsford Island, and City of Boston records do not indicate funding dedicated to the excavation and reinternment of veteran graves at this point in time. It is possible that those 79 veterans, as well as countless others, remain buried on Rainsford Island.

To learn more about the Bell Post G.A.R., visit the Museum of African American History, which is partly housed within the historic Smith School.

Works Cited

“Bell Post Has Busy Day.” The Boston Globe (Boston), May 31, 1910. Accessed June 12, 2021. https://bostonglobe.newspapers.com/image/430828877/?terms=bell post GAR&match=1.

Cultural Landscape Report, Boston Harbor Islands National & State Park, Volume 2: Existing Conditions, 2017. Boston, MA: Olmstead Center for Landscape Preservation, 2017.

“Faces of the 54th.” National Parks Service. January 22, 2021. Accessed June 13, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/boaf/learn/historyculture/faces-of-the-54th.htm#list.

McEvoy, William A., and Robin Hazard. Ray. Rainsford Island: A Boston Harbor Case Study in Public Neglect and Private Activism. Boston, MA: Privately Published, 2019.

“Robert A. Bell Post, 134, G.A.R. (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service. December 10, 2020. Accessed June 13, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/robert-a-bell-post-134-g-a-r.htm#ftref24.

Sweetser, M. F. King’s Handbook of Boston Harbor. NH: Friends of the Boston Harbor Islands, 2017.