Boston’s Women and the Underground Railroad

Boston’s Women and the Underground Railroad

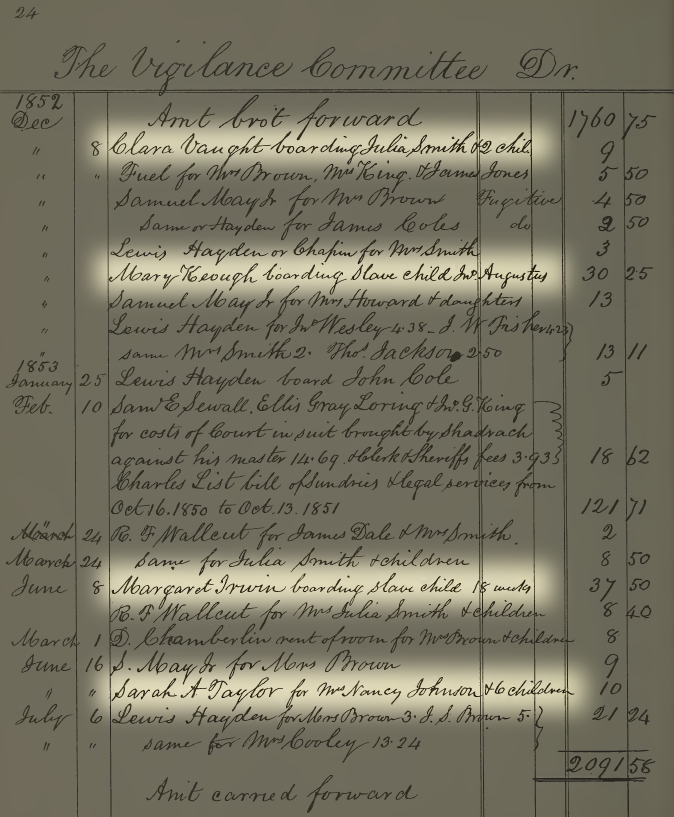

Account Book for the Boston Vigilance Committee with names of women who aided freedom seekers highlighted. (open domain)

Occupying a nearly mythological status in U.S. history, the Underground Railroad was an informal but intricate network of safe houses that led out of slaveholding states in the American South up to free states in the American North and Canada. Comprised of both black and white abolitionists, members of the secret network typically did not know the names of other safe house operators that were located more than two or three towns away from their own safe house.

In the first half of the 19th century, the Underground Railroad evolved from system of aid for freedom seekers, to an intricate, nationwide network of activists determined to aid freedom seekers and defy state and federal laws perceived as unjust. In the decades leading up to the American Civil War, Boston’s women acted as critical contributors to the Underground Railroad by bearing witness to the effects of slavery, participating in and founding anti-slavery organizations, and directly aiding fugitives.

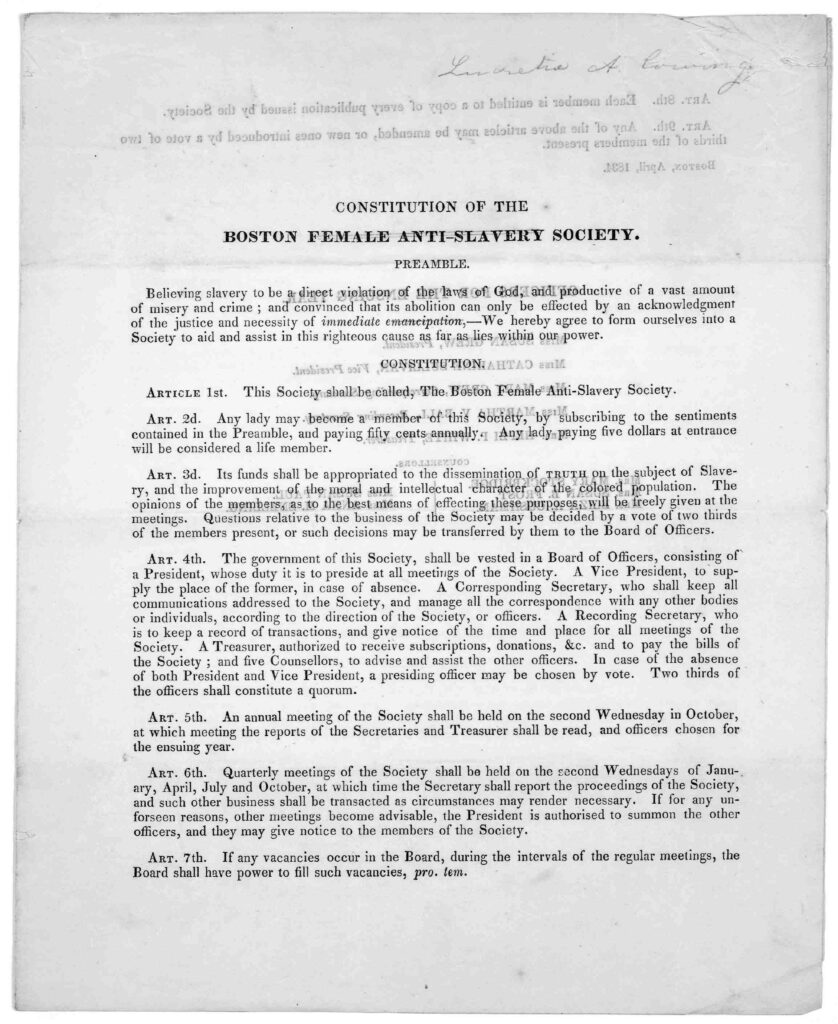

Constitution for Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (Library of Congress)

Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, Boston’s women bore witness to countless events related to the Underground Railroad. These women experienced firsthand the triumphs and failures of Boston’s abolitionist community. As they processed and reflected on these events, the women often recorded their thoughts and emotions, and the reactions and emotions of Boston’s citizenry, in journals or private letters to friends and family. Many of these documents later entered public archives, preserving a public record of women’s involvement with the Underground Railroad. On October 14, 1850, abolitionist Caroline Dall attended an anti-Fugitive Slave Law meeting at Faneuil Hall. She recorded the experience in her journal, writing, “I could not resist going to the meeting at Faneuil Hall in the evening. It was a grand meeting. There was but one feeling among the 6000 persons assembled there, and that was to trample this law under foot.” The presence of these women as witnesses and participants, and their carefully curated records, are tantamount to understanding the operation and impact of the Underground Railroad in Boston.

Women also contributed more publicly though abolitionist organizations. When sexism and societal norms failed to grant women access to certain abolitionist societies, they created their own, recruiting individuals and other organizations open to collaborating with women. During the thirty years preceding the Civil War, Boston’s women joined and founded numerous societies that allowed them to contribute to the Underground Railroad, including: the Afric-American Female Intelligence Society; the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society; the New England Freedom Association; the Boston Vigilance Committee; and the Fugitive’s Aid Society. These organizations raised critical funds to support the Underground Railroad and empowered Boston’s women to provide aid to the freedom seekers entering their city.

Harriet Hayden (Cleveland Gazette, 2/24/1894)

Organizations such as the Boston Vigilance Committee also capitalized on the unique position Black women occupied in society, using it to enable the rescue of freedom seekers stowed away on ships in Boston Harbor. When ships suspected of carrying stowaways arrived, they were often met by a “Committee of Reception,” which stood ready with food and clothing, and provided a carriage to transport freedom seekers north of the Canadian border. Black women served as critical members of these “Committees of Reception.” As Vigilance Committee member Thomas Wentworth Higginson recalled, “The practice was to take along a colored woman with fresh fruit, pies, &c – she easily got on board & when there, usually found out if there was any fugitive on board; then he was sometimes taken away by night.” Captains rarely perceived black women as threats, allowing these women to play crucial roles as operatives on the Maritime Underground Railroad.

Other freedom seekers arrived in Boston and remained, for a period of time, at safe houses scattered throughout the city. These safe houses were operated primarily by women, who provided, food, clothing, orientation to the city, and a place of refuge. Women such as Harriet Hayden and Clara Vaught routinely welcomed freedom seekers into their homes, later receiving reimbursement for the expenses by the Boston Vigilance Committee. The selfless determination of these women to aid freedom seekers, whether by attending a major anti-slavery event, founding an anti-slavery organization, or welcoming a stranger into their home, forever changed the landscape of the Underground Railroad and elevated its reach and success in Boston and the United States.