Escape from the Fort

A question Rangers hear from time to time from visitors at Fort Warren on Georges Island is “did any prisoners escape?” and the answer is mixed. While there are accounts of a few prisoners that did escape from the island, they were ultimately unsuccessful. Georges Island is seven miles from Boston, located in The Narrows, the main shipping channel. Fort Warren was built in response to the War of 1812 to defend the Narrows and Boston Harbor when much of the eastern seaboard was unprotected. During the Civil War, the fort was used to house not only troops that were in training, but also Confederate political and military prisoners of war, and Union deserters and bounty jumpers. Although Fort Warren was known for its humane treatment under the guidance of Colonel Justin Dimick, a prisoner will still long for freedom. “The Lady in Black,” a legend immortalized by Edward Rowe Snow, is one tale of an attempted escape from the fort.

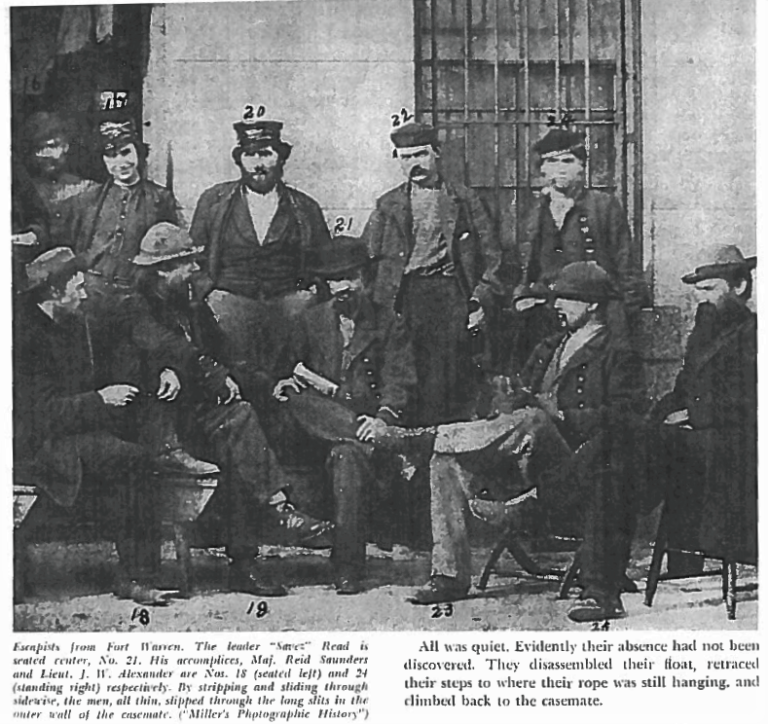

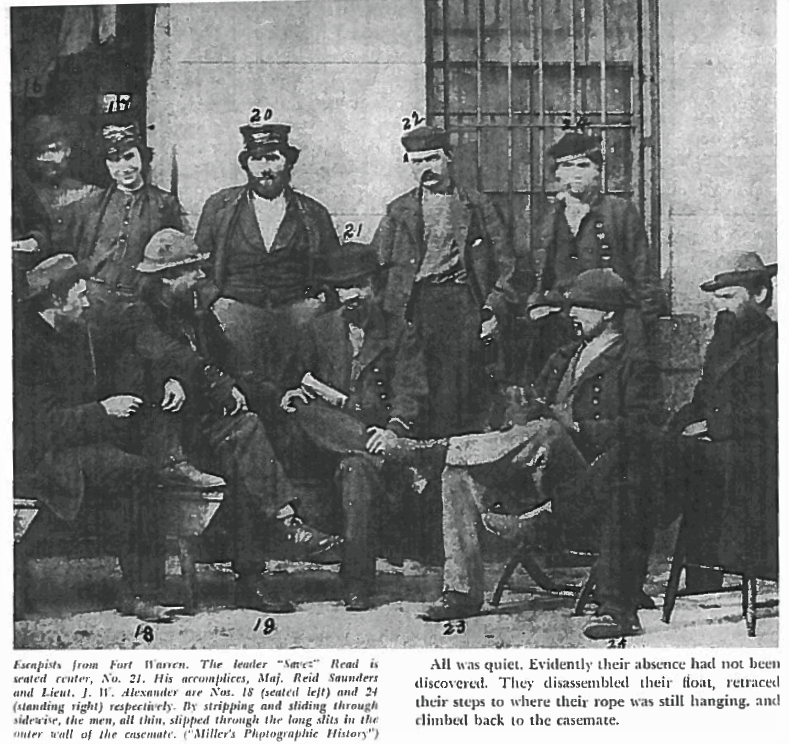

[A group of prisoners sits outside of their room: Lt. Charles Read is listed as 21; Cpt. J. W. Alexander is listed as number 24, and Maj. Reed Sanders is listed as number 18 (respectively): Civil War Times Illustrated]

Fort Warren had its share of famous prisoners; of those prisoners, Captain Joseph W. Alexander of the CSS Atlanta, an iron steamer used to run the blockade into the Savannah River, and Lieutenant Charles W. “Savez” Read (sometimes Reed) of the CSS Tacony, a Confederate cruiser ship, were both captured in June 1863. Alexander recounted his escape attempt years later. Alexander was placed in a casemate under the main battery, believed to be Front III, near the sallyport. Casemates are rooms protected by a vaulted and multi-arched roof structure that support the weight of earth and cannon. Alexander was placed with Read, Lieutenant of Marines James Thurston (CSS Atlanta), and a prisoner from Kentucky, Reed Sanders (sometimes Reid Sanders or Saunders); all of whom were determined to escape. “Many plans were suggested and discussed, but none seemed feasible. Indeed, situated as we were on an island, and strictly guarded day and night, with sentinels stationed in front of our doors, confined within solid masonry constructed to resist the shot of the heaviest guns, it seemed impossible to escape; and yet the escape was easily accomplished” (Alexander 209). Near a pump in the basement where they obtained water, they noticed musketry loopholes that led to an outer wall. These loophole windows were between six to eight feet high, two to three feet wide on the inside, and six to seven inches wide from the outside. It occurred to Alexander, that by turning his head, as if to look over his shoulder, he could squeeze through with some difficulty. However, it was impossible to do so with clothing on. The other three, now aware of this, made hast to escape and waited for a dark night. On August 16th, after sneaking out of their casemates and using a rope to assist them, they dropped into the dry ditch, roughly fifteen feet below, crossed over the cover face and through the grass. Before making it to the seawall, they noticed sentinels on duty. Watching the guards’ routine and timing it just right, they were able to slip past them. Making it past the seawall and observing high winds and rough seas, they agreed that it would be too dangerous to venture that evening and snuck back to their casemates.

[Chart of the Narrows (Main Ship Channel) featuring Georges Island and Lovells Island: Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center]

On the second attempt the following night, Lieutenant Read suggested that two of his men, Thomas Sherman and J. N. Pryde, who were good swimmers, swim to a nearby island, secure a boat and return within a short distance from the shore. Making their way to the seawall as they had the night before, Sherman and Pryde swam off and were never seen again. Alexander states that he heard these men made it back to the Confederacy, but it is believed that they drowned. After waiting for some time, Alexander and Thurston decided they would swim to over to a nearby island, get a boat, and return for Read and Sanders as they were not good swimmers. It is believed that they swam to Lovells Island, 1500 feet from Georges Island, separated by the Narrows Channel. Past the seawall of Georges Island, on the beach, was a large pine board target used for artillery practice. Alexander and Thurston dragged it to the water to use while escaping the island. One sentry–noticing the target was missing–looked over the edge of the seawall and lowered his bayonet down towards the water, believing he saw something in the shadows. The bayonet slowly came to a rest on Read’s chest, but he never moved. The soldier removed his bayonet and commented that he didn’t want to stick it in salt water and concluded that “spirits had taken [the target] away” (Alexander 210). Swimming to the island and coming across a small fishing boat, Alexander and Thurston, dragged it to the beach. As they went towards Georges Island to retrieve Sanders and Read, daylight was breaking, and it was getting lighter. Carrying on without them, they set on for New Brunswick, Canada. They later found out that Sanders and Read had been captured while trying to return to their casemates and were placed in close confinement. Sailing for a day with no provisions, they had made their way to Rye Beach, New Hampshire, and came across a man who lived nearby and asked him for something to eat under the guise that they were from Portsmouth and everything they owned had blown overboard. The man returned with clothes, tobacco, cherry brandy, and food. They told the man they planned to spend the evening in town, but quickly sailed off for Eastport, Maine.

[Lovells Island as seen from Georges Island: NPS McDonough]

Not everything was quiet at the fort. Colonel Dimick was alerted that was an escape and two men were caught. Immediately taking rollcall, he discovered that four men were missing. Dimick asked a steamer heading to Boston to notify the Boston Chief of Police and the Army’s Federal Provost Marshall. Two days later with little breeze to move them along, they Alexander and Thurston were approached by the Revenue Cutter, Dobbin, of Portland, Maine, and asked a series of questions. They were almost released, until someone suggested to search them; Thurston was found carrying Confederate money. They were turned over to the U.S Marshall who brought them to Portland City Jail. The jail soon grew with visitors wanted to see these “’Rebel’ prisoners,- or pirates” (Alexander 212). Staying in the jail for about a month, Alexander and Thurston formed a plan to escape by sawing the iron bars in the washroom and flee to Canada. They were transferred back to Fort Warren before much progress could be made.

Returning to Fort Warren and placed in close confinement, Colonel Dimick allowed them to stay with other prisoners if they would give their word not to attempt to escape, but they declined, as they were once again planning another escape. These plans were scrapped as they were placed in their former casemates with other naval officers, but new plans were once again in the works. Since newly installed iron bars prevented them from escaping through the loopholes they used in the past, they considered the two stack chimneys in their room; connected by two flues, one for their casemate, and the other for the adjoining one. The plan was to move the partition in one of the chimneys to get out of the top. The prisoners took turns each night removing bricks to allow one man to get into the fireplace. To hide the bricks they removed, they crushed them to dust and sprinkled the dust in their morning slop, while replacing the more noticeable missing bricks with bread using dough for mortar and whitewashing the bricks over every morning. After doing this for several months and finally reaching the top, they found a sentinel was stationed at the top of the chimney. In September 1864, they received orders they would be exchanged and were transferred from the fort.

[Demilune: NPS McDonough]

Thurston and Alexander were not the only ones to escape. Union deserter, Private Charles Sawyer from Maine, escaped from the demilune in October 1863. The demilune is a semi-circular defensive fortification located outside the sallyport. It is believed that Sawyer lit newspapers or coals to heat the granite at the loophole window and splash cold water on it to crack the stone. Finally making an opening big enough to squeeze through he then would have landed in a ten-foot-deep dry ditch that protected the demilune. Escaping the island, he was able to swim to a nearby boat. It is not known how far he traveled before being his true identity was discovered and he was sent back to Fort Warren. When he returned, he was placed back in his former room with an iron bar in placed in the window. The iron bar and the cracked granite can still be seen today.

[Loophole window from Demilune. The bottom is wider is noticeably wider and an iron bar can be seen: NPS McDonough]

Fort Warren would eventually house over 2,200 prisoners. Perhaps it is location of the island that there were only a handful of escapes. “Did any prisoners escape?” Absolutely. Were they successful? Successful in getting off the island, perhaps, but they would eventually return.

Works Cited

Alexander, Cpt. J. W. “The New England Magazine. New Ser.:V.7 1892-1893.” HathiTrust. Cornell University, January 13, 2017. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924080787538&view=1up&seq=216&q1=escape.

Bolles, John A. “Escape from Fort Warren .” Civil War Times Illustrated Volume V, Number 4 (July 1966).

E.P. Dutton (Firm), and Boston Map Store. “Chart of Boston Harbor and Massachusetts Bay.” Map. 1865. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:wd376676m (accessed July 07, 2021).

Schmidt, Jay. Fort Warren: New England’s Most Historic Civil War Site. Amherst, NH: UBT Press, 2003.