Shutter Island

A small hill covered in trees sits in the middle of an expanse of water. Several structures are visible near the shore, including three red brick buildings, a white church, and a wooden dock. This is an actual photo of Peddocks Island, one of the filming locations for Shutter Island. (Image Credit: NPS)

Do you like scary stories? In 2010, acclaimed director Martin Scorsese ventured out to Peddocks Island to film part of his frightening thriller, Shutter Island.[1] Peddocks is home to the remains of historic Fort Andrews. With a bit of movie magic, the remains of the fort made the perfect spooky setting for the Ashecliffe Hospital for the “criminally insane.” The movie’s star-studded cast includes Leonardo DiCaprio, Mark Ruffalo, Ben Kingsley, and Michelle Williams. The story follows Teddy Daniels (DiCaprio), a federal marshal in the 1950s, as he investigates a missing person case on Shutter Island, located within the Boston Harbor. During the movie, Daniels learns that psychiatrists at the hospital treat patients through a combination of medication, therapy, and in some cases, through lobotomization.

While Shutter Island and the hospital depicted in the film are both fictitious, they are based in some truth. Islands throughout the Boston Harbor have been home to many social welfare institutions over the years. These include quarantine stations, prisons, almshouses, and hospitals. Long Island Hospital was established in the harbor in 1893 and was operational until the mid-1900s. Over the course of its existence, this institution served as an almshouse, hospital, home for unwed mothers, homeless shelter, and treatment center for people suffering from alcohol addiction. This is the hospital that inspired Shutter Island.

There is no evidence that lobotomies occurred at Long Island Hospital, as they did in Shutter Island; however, there were reports of other forms of mistreatment. In 1903 alone, the hospital faced accusations of poisoning patients with strychnine, neglecting patients in need of medical assistance, and providing insufficient or otherwise unacceptable food for the patients.[2] There was at least one alleged assault, and multiple complaints of an insufficient morgue at the hospital. Most of these issues were dismissed by the Massachusetts judicial system, but the fact that so many concerns made their way to a court of law is notable.

A black and white photo shows rows of hospital beds. This is the men’s dormitory at Long Island Hospital in 1929. (Image credit: Boston Archives)

Fortunately, the medical profession has come a long way in the last century. Today, hospitalized patients and people with disabilities have laws that protect them from mistreatment and inequity, largely due to their own self-advocacy or that of loved ones. Some of these protections include the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990[3] and the American Hospital Association’s Patient’s Bill of Rights (1992).[4] But despite these legislative protections, disability, mental illness, and chronic illness are still stigmatized within American society. This is demonstrated by films like Shutter Island, which portray mental illness in particular as something to be afraid of. In reality, the scariest story is how patients and people living with disabilities and illnesses have been treated throughout time.

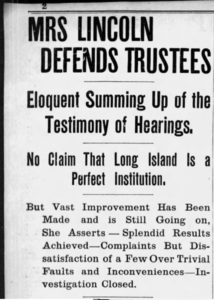

A newspaper headline reads “Mrs. Lincoln Defends Trustees—-Eloquent Summing Up of the Testimony of Hearings—-No Claim That Long Island Is a Perfect Institution—-But Vast Improvement Has Benn Made and is Still Going on, She Asserts—Splendid Results Achieved—Complaints But Dissatisfaction of a Few Over Trivial Faults and Inconveniences—Investigation Closed.” (Image Credit: Boston Globe)

[1] Scorsese, Martin, Arnold W. Messer, Bradley J. Fischer, and Laeta Kalogridis. Shutter Island. United States: Paramount, 2010.

[2] The Boston Globe. 1903. “Mrs. Lincoln Defends Trustees. Eloquent Summing Up of the Testimony of Hearings. No Claim That Long Island is a Perfect Institution.” September 2, 1903, 2. https://bostonglobe.newspapers.com/image/430659590/

[3] “New on ADA.gov,” ADA.gov homepage, accessed October 9, 2020, https://www.ada.gov/.

[4] “AHA Patient’s Bill of Rights,” APRA, August 12, 2020, https://www.americanpatient.org/aha-patients-bill-of-rights/.