Rainsford Island

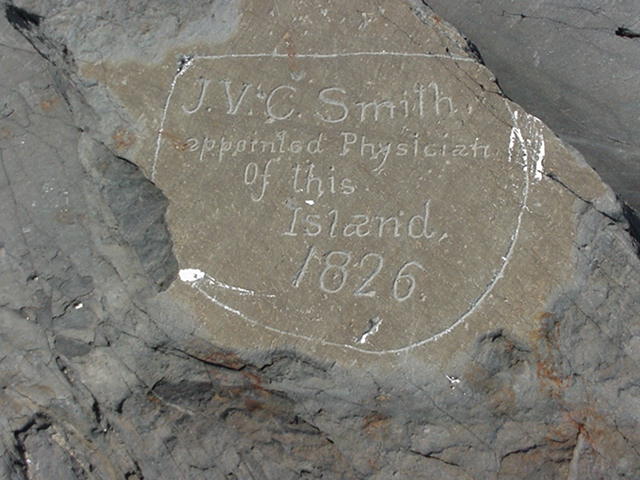

Engraved rock found on Rainsford Island. Photo Credit: NPS.

Boston’s Harbor Islands have served naturally as places to isolate throughout Boston’s 400-year history. As the town grew from its founding in 1630, it became a center for trade, and ships began to arrive from all over the Atlantic world, bringing people, cargo, and disease. While germ theory wasn’t fully understood until the mid-1800s, port cities had begun to quarantine or isolate incoming cargo ships as early as the 1400s in an effort to stem the spread of disease. Spectacle Island was the first quarantine island that established “pest houses” for those who were ill on-board ships approaching Boston.

By 1737, the Spectacle Island quarantine station and a more fully equipped hospital moved to Rainsford Island. Incoming ships were required to quarantine here if anyone on board was ill or if they sailed from a port with a known outbreak of a contagious disease.

An outbreak of yellow fever in 1799 was successfully thwarted when the Boston Board of Health required all ships approaching Boston from foreign ports be boarded and inspected for the disease. Anyone with symptoms was treated by Dr. Thomas Welch, who along with his care and improved sanitation in Boston proper spared the town from a major outbreak.

Aerial photograph of Rainsford Island. Photo credit: NPS.

By the mid-19th century, the focus of care on Rainsford shifted from the quarantine of incoming vessels to the isolation of indigent and ill immigrants, and a hospital was built to house them. The hospital quickly became a place for the local police to “dump” anyone they wanted to keep out of sight and out of mind, and in 1866 an inspector deemed it more of an almshouse than a hospital. During a 12-year period, over 7,000 people were housed there and 875 died from a variety of diseases such as smallpox, cholera, consumption, and other diseases. Over half of them were Irish. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts closed the hospital in 1866, concluding that it had been “misused.”

Starting in the 1840s, Irish immigration exploded in Boston due to a disease that killed the potato crop which the populace depended upon for their primary sustenance. Tens of thousands of starving people descended upon Boston and other port cities along the Eastern seaboard. Although the people of Boston raised money and supplied a ship to take critical supplies to Ireland, the refugees who fled to New England did not receive the same charity. These people were poor and Catholic and not welcome in Protestant Boston. Although thousands served their new country as soldiers in the Civil War, they were still considered a ”problem” to be dealt with, and Rainsford was once again transformed to a place where “adult pauper males” were sent to literally break rocks which were used in construction. Between 1872 and 1889, 771 men died of Phthisis (pulmonary tuberculosis) and buried on Rainsford with 200 of them being under the age of forty.

By 1889, the Men’s Alms House was overpopulated, and they were moved to Long Island. They were soon replaced by another disenfranchised group: women. Poor and sick women were sent to Rainsford and endured underfunded and unsanitary conditions. Although these women were ill, they were expected to cook and clean for themselves with minimal resources. Conditions at the facility were so appalling that in 1894, activist Alice Lincoln filed a formal complain to the City of Boston Board of Aldermen. After nine months of testimony as to the horrific conditions at the women’s hospital on Rainsford, the City closed the facility which had operated for five years, but not before 166 women and 16 infants, including 11 born there, had died.

Aged stone cross stands in the grass on Rainsford Island. In total, it is estimated that 1,777 individuals are interred on the island today. Photo credit: NPS.

Despite its cruel history of isolating under-represented groups of people in a variety of institutional settings, Rainsford has experienced a small number of bright spots, such as stopping the spread of yellow fever in the early 1800s, and providing a wholesome open air facility for infants and young children who often died of bacterial infections from spoiled food in the summer months. Now, as Boston moves into its 5th century, Rainsford is moving in a new transformational direction. Our ability to understand the impacts of climate change rely in part on the study of fragile ecosystems and the changes they’ve undergone in the past 100 years. The shoreline erosion of Rainsford has been studied in great detail, and these results will benefit management decisions and greater understanding of climate change for future years. Our partners at the Stone Living Lab will continue this research at Rainsford through careful monitoring. To learn more about these efforts, visit https://stonelivinglab.org/.

Bibliography

Centers for Disease Control and Protection, “History of Quarantine.” Online.

McEvoy, William and Ray, Robin Hazard. Rainsford Island: A Boston Harbor Case Study in Public Neglect and Private Activism. Independently published. 2019.