Juneteenth

Black Heritage and Boston Harbor Part 1: Juneteenth

For many Americans, July 4th is a day to celebrate freedom and independence as a nation. However, for nearly a century after this day in 1776, millions of people across the newly formed country remained undeniably without freedom. At the time that the Declaration of Independence was written and through the end of the Civil War in 1865, the institution of slavery was widespread across America, and many viewed it as acceptable and essential to maintaining the economic and moral integrity of the young nation. With the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the passing of the 13th Amendment in January of 1865, and the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox Courthouse two months later, the Civil War formally came to an end and—in theory—all enslaved people gained their freedom. In reality, news of these triumphs took several months to officially reach some of the far-flung corners of the Confederacy, with Texas being the last state along the message route.

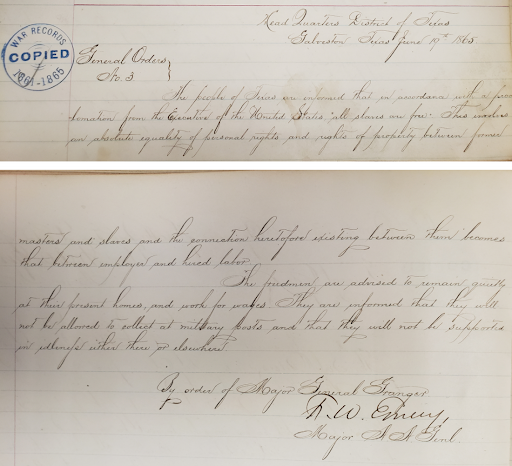

On June 19th, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger of the United States Army issued General Order No. 3 in Galveston, Texas, making it known that,

“…in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

General Order No. 3, issued by Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger, June 19, 1865. The order was written in a volume beginning on one page and continuing to the next. (RG 393, Part II, Entry 5543, District of Texas, General Orders Issued)

National Archives

The 19th of June, also known as Juneteenth, Freedom Day, and Emancipation Day, has been celebrated and remembered ever since as the true end of slavery in America. But this day does not stand alone in history. This article is the first in a series that will explore the events leading up to this historic event and beyond. Stay tuned to future e-newsletters and to Boston African American National Historic Site’s website to learn more.

Emancipation and the Formation of Black Regiments

“Once let the Black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship in the United States.”

-Frederick Douglass, 1863

In January 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This stated that, “…all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” The proclamation also permitted and encouraged free Black men to serve in the Union Army and Navy. This call to arms resonated across New England, including in the Boston area, leading to the formation of two of the first all-Black regiments in the nation.

Shortly after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, abolitionists like Frederick Douglass and Lewis Hayden began recruiting Black men across New England and the country to enlist in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The company mustered out of Boston in May of 1863, marching through the streets of the city singing “John Brown’s Body”– a song popularized by other regiments at Fort Warren on Georges Island in the harbor, and which later evolved into the Battle Hymn of the Republic. The 54th traveled to South Carolina, where they fought heroically in the Battle of Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863. The bravery of the men at this battle in particular helped inspire the enlistment of more than 180,000 Black men, who became an invaluable, driving force in the Union Army.

“The 54th Massachusetts regiment, under the leadership of Colonel Shaw in the attack on Fort Wagner, Morris Island, South Carolina, in 1863,” mural at the Recorder of Deeds building, Washington DC

Library of Congress

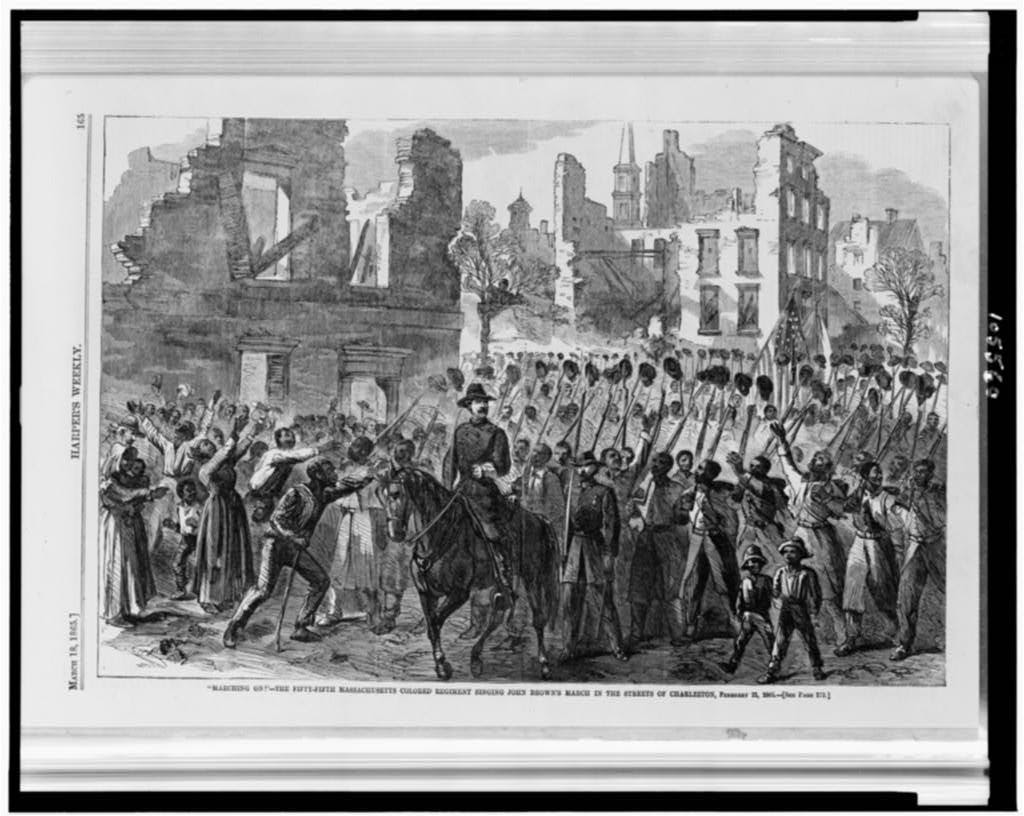

“”Marching on!”–The Fifty-fifth Massachusetts Colored Regiment singing John Brown’s March in the streets of Charleston, February 21, 1865,” published in Harper’s Weekly

Library of Congress

With so many men enlisting, new regiments were formed, including the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Like the 54th, this was an all-Black regiment based out of Boston. In 1864, the 55th served on the frontlines in Florida and South Carolina, continuing to occupy the latter through the summer of 1865, after which they returned to Boston via Gallops Island.

Gallops Island in Boston Harbor served as a discharge post for units returning from various parts of the country. The 54th and 55th regiments, as well as the 5th regiment calvary—another unit comprised of Black volunteers—all passed through this island stop upon completion of their duties. These units fought for freedom, carrying messages of hope for future generations. Not everyone who enlisted in these groups returned through Gallops Island. Many lives were lost. But news of their sacrifice and its significance carried across the nation and continues to echo across time.

Juneteenth Origins, Significance, and Observance

In June of 1865, as the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment occupied the newly emancipated Charleston, South Carolina, news of the end of slavery spread across America. Texas, the westernmost state of the Confederacy, was the last to receive this news. On June 19th, 1865, enslaved African Americans in Texas finally received word of the end of slavery. This news came over two years after the Emancipation Proclamation, and two months after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia.

Many people who celebrated the end of slavery were met with hatred and violence. Racist structures deeply rooted within American government, economics, and culture permitted and even supported these types of reactions after the Civil War. They continued through Reconstruction, and well into the Civil Rights Era of the 1960s. In many ways they still pervade society today. Despite the threat of violence, Black Americans have celebrated Juneteenth since 1866 as an act of defiance, as a declaration of independence, and as a statement of pride in Black heritage, culture, and community.

Emancipation Day Celebration Band, June 19, 1900, Austin. Photo by Mrs. Grace Murray Stephenson.

Austin History Center, Austin Public Library

Emancipation Day, 1913. Corpus Christs, Texas. Photo by George McCuistion.

DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

Today, 47 states and the District of Columbia recognize Juneteenth as a state holiday. Texas, the last to learn of the 13th Amendment, became the first state to officially recognize the holiday in 1980—more than one hundred years after the first celebration. Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick—the first Black governor of the Commonwealth—signed a bill in 2007 recognizing Juneteenth. In 2020, in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, Governor Baker reinforced the proclamation by declaring Juneteenth an official state holiday.

Today, the National Parks of Boston continue to expand their research and communication to engage visitors with inclusive, diverse, and accurate representations of historical narratives that have traditionally lacked Black voices. To learn more about Juneteenth and Black history in the Boston area and across the country, visit the resource list below. Sign up to receive Boston Harbor Islands e-newsletters and be the first to read the next installment of this series, focusing more closely on the African American experience on Gallops Island.

Freedom Day March, Juneteenth 2020. Photo by Manuel Balce Ceneta.

AP Images

Resource List

Boston African American History

Boston African American National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

MAAH.org | Museum of African American History | African Meeting House | MAAH

African American Heritage National Parks and Monuments

Visit – African American Heritage (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

African American Sites – Travel America’s Diverse Cultures (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

Juneteenth: A Celebration of Freedom (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov)

Bibliography

“A Brave Black Regiment: The 54th Massachusetts.” National Parks Service. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/boaf/learn/historyculture/a-brave-black-regiment.htm.

Anderson, Derek J. “Juneteenth Officially Recognized As Mass. Holiday.” Juneteenth Officially Recognized As Mass. Holiday | WBUR News. WBUR, July 25, 2020. https://www.wbur.org/news/2020/07/25/juneteenth-officially-recognized-as-mass-holiday.

“Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration, September 1, 2017. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war.

Ceneta, Manuel Balce. [Juneteenth Washington], photograph, June 19, 2020; (www.apimages.com/metadata/Index/Juneteenth-Washington/ec5d206f78544fc08222ea44e01ff365/8/0 : accessed May 18, 2021), Associated Press.

Davis, Michael. “National Archives Safeguards Original ‘Juneteenth’ General Order.” National Archives and Records Administration. June 19, 2020. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/news/articles/juneteenth-original-document.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. On Juneteenth. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a Division of W. W. Norton & Company, 2021.

Kendi, Ibram X. How to Be an Antiracist. London: Vintage, 2020.

Kimball, George. “Origin of the John Brown Song.” The New England Magazine, 1889-1890, 371-76. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101064987934&view=1up&seq=385&size=150.

Lincoln, Abraham. The first edition of Abraham Lincoln’s final emancipation proclamation. Washington, D. C., January 1, 1863. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/scsm001016/.

McCuistion, George. [Emancipation Day, 1913. Corpus Christi], photograph. June 19, 1913; (https://digitalcollections.smu.edu/digital/collection/tex/id/2422 : accessed May 18, 2021), DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Emancipation Day, 1913. Corpus Christi, Texas – Texas – Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints – SMU Digital Collections.

Stephenson, Mrs. Charles (Grace Murray). [Emancipation Day Celebration band, June 19, 1900], photograph, June 19, 1900; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth124054/m1/1/?q=emancipation: accessed May 18, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Yared, Ephrem. “55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (1863-1865).” BlackPast. February 07, 2020. Accessed May 17, 2021. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/55th-massachusetts-infantry-regiment-1863-1865/.