Colonial Wading Birds

You may have seen their cousin, the Great Blue Heron, standing tall in a marsh or wetland somewhere, but have you ever seen a Great Egret? Those of you who spend time in and around Boston Harbor during the spring and summer months may have noticed these strikingly tall white birds hunting for food in salt and freshwater wetlands close to the islands. Great Egrets are considered wading birds because they feed by wading into the water, and if you’ve seen one, it was likely along the shoreline, frozen still, long legs partially submerged, waiting intently for a small fish or amphibian to come within reach of its long, pointed bill. But have you also noticed the smaller Snowy Egret patiently stalking prey amidst the tall marsh grasses, or the secretive Black-Crowned Night Heron flying off to forage between dusk and dawn? All three of these wading birds actually nest on the Boston Harbor Islands during spring and summer, and forage in nearby coastal wetlands, but fewer people tend to notice the latter two species. This is partly because they are smaller and more secretive than the Great Egret, but is also due to the fact that the Boston Harbor populations of Snowy Egrets and Black-Crowned Night Herons have been continuously declining since the 1990s.

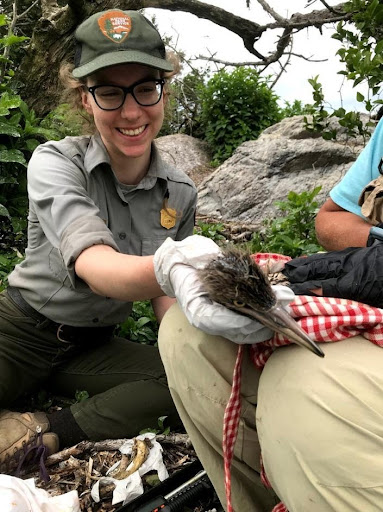

In partnership with the National Park Service and the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, Mass Audubon’s Coastal Waterbird Program has embarked upon a two-year scientific investigation of these populations of wading birds in order to try to shine light upon the reason for their continued decline. The overarching goal of this investigation is to determine the primary factors driving and impacting reproductive success of colonial nesting wading birds on the harbor islands. Armed with the data gleaned from this investigation, island managers and ecologists can work together to implement management strategies that promote reproductive success and population recovery.

Conducting research on nesting herons is an experience unlike any other, in large part because of their manner of nesting. Herons and egrets are part of a group of birds collectively known as colonial-nesting wading birds because of their pattern of establishing large breeding colonies during nesting season and their behavior of feeding by wading into the water to catch their prey. A colony of nesting wading birds is a loud, active, densely-packed scene, with constant clucks and grunts and prehistoric-sounding calls passing back and forth between its long-legged inhabitants. It is much like a busy city, where each tree is an apartment complex full of nests, and where noisy neighbors constantly negotiate and renegotiate the terms of peaceful coexistence.

Nesting in such a colony is a successful behavioral strategy, because it means that there are plenty of eyes to look for predators and plenty of voices to sound the alert when necessary. It is the embodiment of the “strength in numbers” philosophy. In order to maximize reproductive success, a large colony would ideally be established on a predator-free island that lacks human disturbance, has suitable vegetation for placing nests, and is close to wetlands providing invertebrates, fish, and amphibians to eat. However, ideal conditions are hard to come by, and colonial nesters are facing increasing pressure from competition with humans who love to live and play on the islands of coastal New England. Additionally, there is ongoing alteration and loss of wetlands both here, near nesting areas, and in Latin America, on wintering grounds.

So, what can a poor heron or egret do? Enter the Boston Harbor Islands. Thanks to their status as a National and State Park, the Boston Harbor Islands offer uniquely protected habitat for the establishment of nesting colonies. Currently, herons and egrets take advantage of five of the islands to do so. Different species often come together to nest within the protection that a colony affords, and you might see Herring Gulls, Great Black-Backed Gulls, Double-Crested Cormorants, and Glossy Ibises nesting in and around the heron colony as well. Entering a colony to collect data involves intimate immersion into this diverse and multilayered city of birds, while taking the strictest of precautions to minimize additional disturbance to their complex seasonal community.

The data we collect include measurements of eggs as they are laid and chicks as they grow. We enter the colony to weigh and measure chicks in our study nests several times a week. Additionally, we monitor chicks for skin lesions, survey the vegetation chosen for nest sites in the colony, note the location of preferred foraging grounds, and deploy cameras to detect predation and disturbance. Over the fall and winter, we will analyze the data we have collected and refine our efforts for the 2022 field season. Ultimately, this investigation will increase general knowledge about the Boston Harbor Islands wading birds, their population dynamics, and the pressures they face at their nesting sites. By the end of year two, we aim to have collected enough data to be able to identify the variables that have the greatest impact on reproductive success. This will help island managers, biologists, and ecologists to develop management strategies to support population recovery efforts for the Boston Harbor Islands wading birds, and hopefully reverse the declining trends.